As we are about to start the planning meetings for 2024, I’ve been thinking a lot about how I take notes. In the same vein, the process of putting together a keynote takes months, and it means that I’m meeting with a lot of smart folks doing research and building amazing products. And at every meeting I’m taking notes—lots of them.

The earliest memories I have of taking notes are in primary school. I would copy word-for-word what the teacher would say or write on the board. Then I’d go home, study what I’d copied, and eventually take a test. In practice, I was learning to encode, store, and recall information. When you think about it, it’s a bit like our Simple Storage Service, S3.

But this was memorization, not synthesis.

As I continued along my educational journey, and the subject matter increasingly became more complex; it forced me to rethink note-taking. It was less about being a scribe, and more about listening, observing, and comprehending what was being taught.

For example, the younger me may have copied the following definition verbatim: “The classic role of mitochondria is oxidative phosphorylation, which generates adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by utilizing the energy released during the oxidation of the food we eat.” When studying, I would have committed this to memory without necessarily understanding how it actually worked. It would have been more helpful to read the definition, then write it out in a way that was meaningful to me, such as: “Mitochondria are the power plant of the cell. They generate most of the chemical energy needed to power the cell’s biochemical reactions.” Maybe even diagram the process in the margins. This is synthesis. This denotes understanding.

There’s research to back this up. Specifically, that verbatim note-taking just isn’t as effective when you’re trying to learn and retain new information.

The Cornell Method

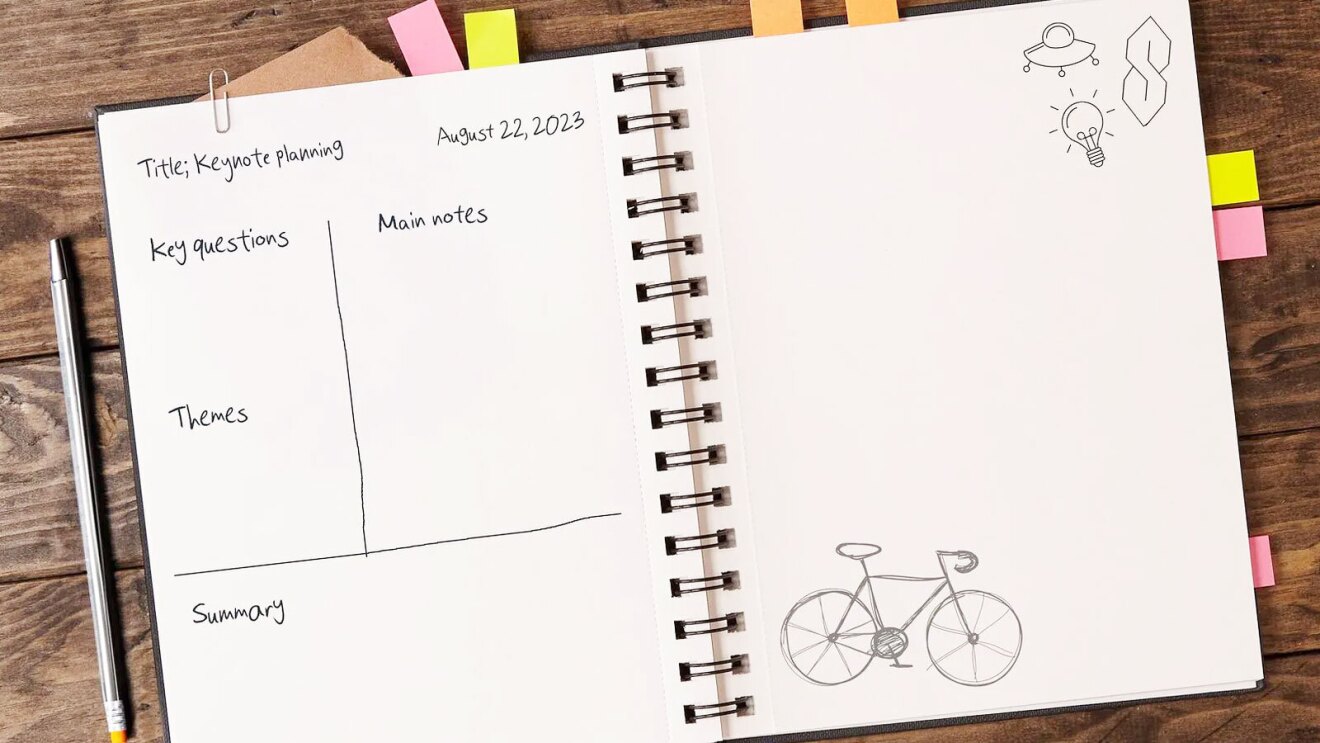

I’ve spent quite a bit of time over the last few months reading about and relearning different note-taking approaches. Everything from outlining to mind mapping to charting. And what’s worked quite well for me is the Cornell Method.

It is a simple approach that has you split a notebook page into four parts:

- Title

- Notes

- Keywords and questions

- Summary

And no, it’s not because I worked at Cornell University for the better part of a decade, but because this method encourages you to document your thought processes (i.e., ask questions), synthesize what you’re learning in real-time (i.e., take notes), and summarize it all after the fact (i.e., write a succinct summary).

What I wind up with are structured notes that are easy to read, organize, and revisit, because it’s more than just writing something down, but being able to go back and review questions and challenge assumptions.

A recent study by Kuniyoshi Sakai, titled Paper Notebooks vs. Mobile Devices: Brain Activation Differences During Memory Retrieval, actually showed higher retention and recall for subjects that used pen and paper versus a keyboard, or tablet and stylus. However, there is broad agreement that taking notes, in any form with any input, helps with retention and recall.

Pen and paper

To this day, I still take a lot of notes by hand. It helps me maintain focus and internalize the important bits. It’s impossible to write as fast as people speak, so I’m forced to write down what I think is most important or make note of what I don’t understand so I can ask questions.

I am a big fan of analog note-taking. For me, analog helps with memorizing, synthesizing, and summarizing. As soon as I write something down with pen and paper, it also seems to find its way into my brain—something that doesn’t happen with digital. I even use the Cornell Method when preparing for meetings; I summarize the briefing doc in my notebook, and it immediately sticks. The fact that you are active with the text instead of just reading it drives this process.

Using ML and generative AI

There is a lot of value in the act of taking notes and actively synthesizing information. But we live in a world with more data than we could ever reasonably expect to comb through. This is an area where machine learning (ML) and generative artificial intelligence (AI) will play an increasingly important role. A few examples that come to mind are:

- Using a transcription service with speaker identification to supplement the notes you take during a meeting.

- Using computer vision and optical character recognition (OCR) to convert your handwritten notes into docs that you can easily share with others or store in a central location. (Assuming that you’re not already using something like Kindle Scribe).

- Near-instant summarization.

- Iterating over an entire corpus of notes using a large language model (LLM) to identify themes, trends, and important people across hundreds of pages from meetings, lectures, doc reviews, on-site visits, etc.

I see this like reading a map. If you go back 20 years, reading a map was a fairly common skill. You’d plan a route, take some notes, then try to navigate it. And if you took the route enough times, you’d commit it to memory. You’d remember a fountain or the color of a specific house along the way. You’d know when and where there would be traffic or construction, and the alternate routes to get around it. But these days, we just use our phones. We follow turn-by-turn directions from street-to-street without needing to commit too much to memory.

It’s helpful. It’s easy. That’s not really up for debate. But reading a physical map is still a very useful skill. There will inevitably be times that you don’t have cell service (or you lose your phone, or maybe you want to disconnect from technology), and knowing where you are and how to get where you’re going are important. And just like taking notes by hand, it allows you to remove some of the noise created by technology, and to focus on the important bits.

I’m genuinely curious to see how research will evolve in the next 10+ years as we continue to study what works best for digital natives.

Take notes, lots of them

I’ll leave you with a quote from the writer Anne Lamott: “[…] one of the worst feelings I can think of, [is] to have had a wonderful moment or insight or vision or phrase, to know you had it, then lose it.” My advice: take notes, lots of them.

Now, go build!

Want to read more? Check out my personal blog All Things Distributed.